Death said she had something to show me;

What? I wondered—

Pornographic centerfolds of the Dead?

The lost piece of petrified wood

Once mounted in my grandfather’s favorite ring?

It was neither of these things,

Though, in a sense, all and more

And it wasn’t for my eyes

At least not these organic ones

Which perceive in the usual spectrum—

Not for these mortal eyes of mine.

She came to me again

Once I was robotic, a cyborg,

Still possessing a human mind

And tattered strips of flesh

Here and there

With eyes of glass like a camera’s lens;

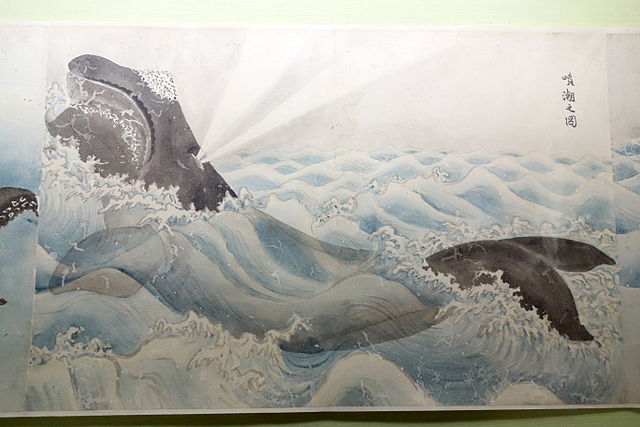

And only then did lovely Death

Reveal her final offering:

A jittering map of sorts,

Glowing and pulsing with infras and ultras,

Dreamlike, nightmarish;

She showed me a blueprint of my soul—

Demented dreams concealed inside

Erasures of memories long denied

So many revelations I did not wish to know.

Broken pathways of indecisions,

Lies and secrets best not told—

Inept choices, foolish revisions

Delineated lines of neural flow—

Nor could I overcome

The horrorshow

And then Death said

She had no regard

For me, whatsoever