Sculpting Science by Mary Alexandra Agner

Mara Haseltine leans over the side of the boat as she lowers the weighted net into the Seine. Haseltine is fishing for plankton, aquatic creatures unable to move themselves through the water. Plankton drift, eating what drifts by them and being eaten by what moves around them. Some plankton are large, such as jellies, but most require a magnifying glass or a microscope to see them.

Haseltine fishes from the 110-foot research schooner Tara. Tara was the vessel for an international effort which sampled and catalogued the oceans from 2009 to 2013, attempting to learn more about Earth’s largest biome––and the one humanity understands the least––through its populations of plankton, including everything from viruses to zooplankton. Research results from its journey won the cover spot as well as interior ink in a recent issue of Science.

Haseltine hauls her nets back up. She preserves some of the samples to look at later. Back home in a lab, she’ll run the samples through a centrifuge, separating out plankton of different sizes. Today she takes a droplet of Seine water straight to the ship’s microscope. Magnifying the droplet, Haseltine finds a night sky scene––-black background with glowing stars––-until she turns the focus knob and the stars sharpen into white squares, chains, trapezoids: the bodies of plankton.

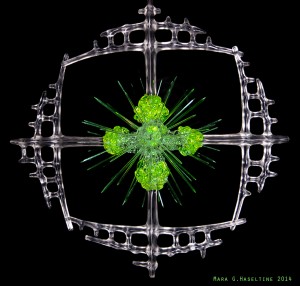

Unlike the other people working aboard Tara, Haseltine didn’t head back to university and write a science paper about what she saw. Instead, she began a series of human-sized sculptures depicting the tiny plankton, culminating in her two-part series La Boheme: Portrait of Our Oceans in Peril. Haseltine’s sculptures are all saturated colors, the clean curves of the plankton contrasted with the ocean detritus that ensnares them. Almost none of the living creatures in her work have escaped the grasp of plastic waste tossed into the oceans by humans.

Though today Haseltine considers herself a conservationist, she says she grew up in her father’s x-ray crystallography lab. It was the plankton she discovered there that created the greatest sense of wonder in her. “It made me realize the enormity of life as we know it depends on these tiny creatures to provide 50% of our planet’s oxygen.”

Every living creature in the ocean eats plankton or eats something that eats plankton. Even land animals are affected. Plankton feed the tuna in the can in your kitchen. Plankton even show up in your car: the remains of plankton turn into gasoline after sinking to the ocean floor, mixing with the rocks below, and being pulverized for millions of years.

To emphasize the importance of plankton, Haseltine’s sculptures magnify them, making the plankton into objects humans can touch. Her sculptures of tintinnids––a plankton shaped like a vase and about the width of a pencil stroke on paper––stand over six feet tall.

Haseltine began her artwork with images of plankton, but she also researched their life cycles, since some plankton morph their bodies as they grow. In the end, she chose uranium-infused glass to sculpt the plankton so that the finished art will glow when lit by ultraviolet light. She says, “While staying true to the anatomy of the plankton, I imbue the work with my emotion. These creatures are so beautiful, fragile, and resilient I want the world to fall in love with them as I have.”

Links

[http://www.calamara.com] Mara Haseltine’s website

[http://www.sciencemag.org/content/348/6237.toc] Issue of Science magazine referenced in the text

[http://www.calamara.com/uncategorized/dumbo-arts-festival-sept-27th-28th/] Close-up of one of Haseltine’s plankton sculptures